Chunking - sounds like techno-babble

By Sarah Frossell

Published in Rapport Magazine Spring 1998

It is. The best sort of technobabble because it's so user friendly. We could call it something else. You can call it something else, when you've mastered it and made it your own. I will continue to call it 'chunking' because I like to attribute what I use and because my clients like it, use it consistently and the word makes them laugh!

What is it? What does it mean. . . ?

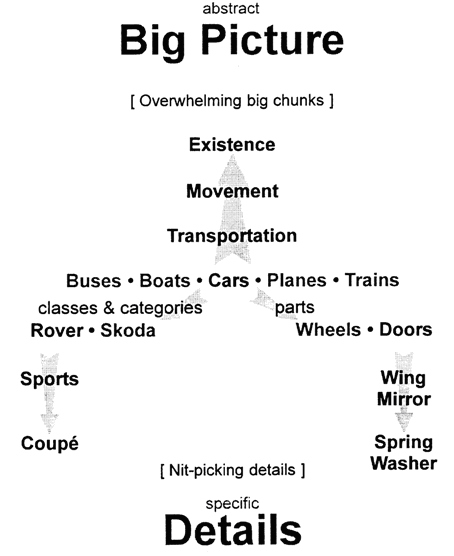

The term 'chunking' comes from the IT industry where people define the 'chunk size of information' with which they wish to work. Sometimes we require information at the 'big picture', 'blue-sky' level. We call this 'large chunk' or'chunked up'. At other times we need to be working at levels of more or less detail. We may consider this to be 'small chunk' or 'chunked down' operating. Simple, isn't it?

NLP has borrowed the term and developed a model which will assist you in learning how to apply an effective chunking strategy to what you do whenever you choose to communicate with others.

You've been using parts of it - we've all been using parts of it - all our lives. You can't communicate without chunking at some level or another. All of us operate at a preferred 'chunk size' or within a range - what I sometimes call 'an envelope of comfort'. Developing our flexibility with chunking, stretching the envelope, will make a positive difference to the ways in which we communicate, negotiate with and influence others.

Why use it . . .?

Let's consider a couple of true stories to illustrate the benefits of becoming more flexible in this arena.

First, imagine this scenario from five years or so ago:

A new MD with a marketing background is brought in to turn round a household name company. Its products are sporting goods involving complex, and in some cases heavy, engineering. It has been a market leader and still has the leading edge on several innovative products. The factory is locked into the past; the market is changing faster than the Board could ever have imagined; new players have entered the field and look to be positioning themselves for a rout.

The Board is made up of engineers and one accountant, specialists in their areas of expertise. All of them, with the exception of the MD have been there for a minimum of twelve years and have lived through a period of unparalleled growth and then the recession of the early nineties. The MD has been finding it impossible to have constructive conversations about the future because the rest of the Board find it impossible to grasp the big picture that he sees only too clearly - that unless they change they will die, that living in their past glories moves the focus away from what they need to do now in order to grow and develop into the future, that companies must be profitable to survive, that there are huge opportunities out there for them which need to be grabbed and worked on now!

He reports that all they want to talk to him about is the detail of their technology. He has told them that he wants to know nothing of the detail - it will only prevent him from looking at the vision of the future that they must create together and that he must drive through.

Secondly, another scenario from 3 years ago:

An inspired, inspiring and intuitive Marketing Director has been headhunted as part of a brand new team developing a newly-created insurance company. The other board members are actuaries and accountants. A few months in and he thinks he is losing his mind.

Whenever he is asked to come up with a marketing plan - which is usually a fairly speedy process for him - the market is transparent and known; their niche is clear and he sees the vision of what they need to achieve very clearly - the CEO insists on making double sure by researching the figures. On average this process takes three weeks, confirms the original plan and then, just to make absolutely certain, the CEO insists on going into some of the figures in even greater depth. Another week or so passes by! The original plan is always confirmed by the figures, but the same or a similar process happens each time there is a decision which needs to be made. The Marketing Director is rapidly losing his ability to see any patterns at all, let alone make suggestions for what the next steps must be.

I could give you dozens of similar examples, all, in my opinion to do with the level at which people do or do not 'chunk'.

In both of these cases the benefits of being able to understand what was going on, or perhaps more specifically, not going on in these communications would have solved the situations internally and much more quickly. Plans that needed to be started would have been put into action straight away. These two individuals and their board room colleagues would have avoided a great deal of stress, been better able to manage decision making, their own jobs and deliver more effectively to the bottom line. All benefits which, I'm sure you would agree, would have been worth having.

The Model . . .

Let's play. Let's say I'm going to buy a car and gear the model up to that.

The chances are that, once I've made my decision, I start to do some research. I may do it 'large chunk', like the Communications Director of a large public company, who simply saw a red one that she liked the look of one lunch-time when she happened to be passing the garage that was displaying it. She hadn't got a clue about what make or model it was. She only knew that it was the one she wanted, and so spent some hours retracing several lunch-time journeys with the fleet manager of the company until she saw it again and could leave him to do the detailed, 'small chunk' research. (Incidentally this is a real example: she was a she and he was a he and I apologise for what may seem to some to be role stereotyping.)

The only thing he knew for certain was that she was mad! He approached the matter in his usual logical mode, spoke to a salesperson, asked specific and detailed questions about the spec, the price and the deals he could do, and then bought it for her, in the right colour and, happily, at an advantageous price to the company.

To do the narrowing down for my car, I will ask several salespeople specific questions like the following:

- Tell me about the specific models you have?

- What specific features does this one have . . . ?

- Give me some detail about the process here . . . how does it work?

- What are its benefits in comparison with X?

- What's the 0-60 acceleration rate?

- How many c.c.s?

- What brand of stereo comes as standard?

And when I'm satisfied, I'll buy the one that most fits my desires.

I have started this process from the premise that a car would solve my transport needs. I'm a consultant. I need to get to see my clients. Consultants have cars. Usually pretty and deadly ones. My processing has started somewhere just above the middle of the chunking model and has moved downwards - an easy progression for me and for most other people in the World.

But, let's consider a different situation. Let's say I've been reading everything I can get my hands on carbon emissions and the government's future transport policies. Let's say that politically and philosophically I do believe that we need to cut down on cars and I wake up one morning wondering if there might be another way.

At this point I start to 'chunk up' and ask myself a different set of questions, ones like this:

- Why do I need a car? What's its purpose?

- How else could I meet my needs?

- Where does having my own car fit in with the bigger picture of saving the planet?

- Do we really need to save the planet?

- Do I need to travel at all?

By chunking up like this I may discover that the issue I really have is one of communication as much as transport. It may be that I'm a closet megalomaniac, care absolutely nothing about global warming and I think, like one of my clients, that the answer is a Lear Jet, or like another, a helicopter. Or it may be that when I really think about it, it would be more convenient to me, more useful of my time to travel by rail or coach, when I could be reading or working, rather than to be sitting in a traffic jam on one of the roads into London or any other of the big cities. Or even that I need to upgrade my technological support and communicate digitally rather than in person.

So what if you were to become a more flexible chunker . . . ?

What would be different? How could you apply the model? How would you have used it to alleviate the problems that I've described with my clients above?

The Marketing Director was reassured that the problem was theirs rather than his. He learned to listen well and leave the rest of the Board to delve into the detail they needed while he did more blue sky thinking and waited for them to catch up. In time they learned the value of his intuition and began to chunk up to his level. Decision-making happened more quickly and ultimately became a process involving all the team's skills.

The MD's issue was simple to resolve. I taught the Board the model. The engineers learned to notice when the MD began to be uncomfortable with what they were saying, and immediately 'chunked up' in order to build rapport with him; in extreme cases the MD himself cued them by sticking his thumb up in the air. The result: forward movement for the company, a speedy return to profitability and much less tension all round.

As the engineers discovered, chunking can be a very powerful tool for rapport building and negotiation. In fact, if you look at the Harvard Negotiation Process you will notice that it is all about deft chunking: match your partner(s), chunk up for agreement and then go into the detail; when you get to sticking points - and you will, that's what negotiation's all about - chunk back up quickly in order to keep rapport and strengthen the feeling of a shared process and ultimate agreement.